A few kilometers beyond Chamonix on the road to Argentiere one passes through the Bois de Favre, a densely wooded forest of silver pines. Suddenly the trees end at a clearing: a rocky terminal moraine where the Mer de Glace had once carved its way slowly past under millions of tons of ice. If one looks up at this point, and it’s hard not to, especially if you’re a climber, it’s the one place along the Arveyon valley that the full immensity of the Petit Dru can be seen. The West Face, wild and jagged, rises out of the timberline for thousands of metres, gradually tapering into a slender needlepoint silhouette that pierces the pale blue sky. It’s an almost perfect granite spire.

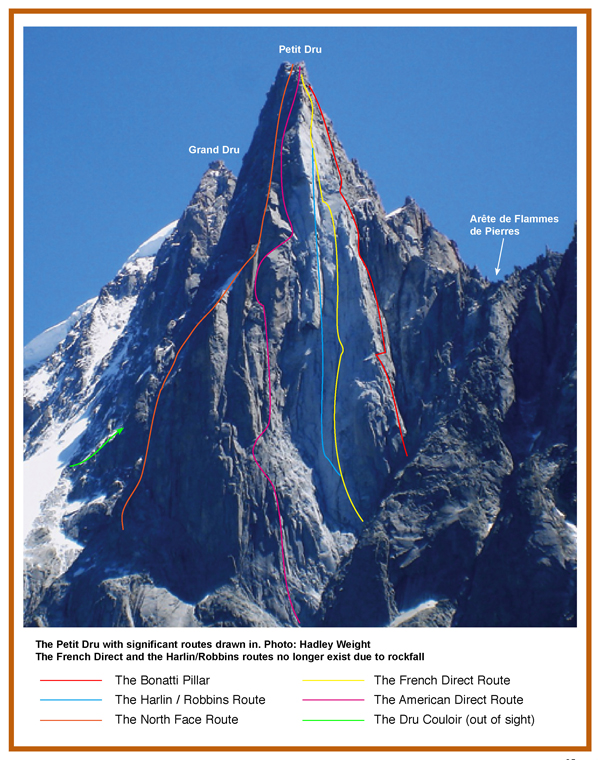

The Dru stands at the end of the line at a geological confluence of great tension. A nine kilometre long serrated ridge starts at Mt Dolent, the point where the borders of France, Switzerland and Italy briefly meet, and continues westward over the Triollet, Courtes, Droites, Aiguille Verte, and the Grand Dru, before it suddenly ends with a heartstopping drop over the edge of the Petit Dru. The Arete of the Flammes de Pierre continues down from here, completing this grueling spine of shattered and unstable Alpine geology into the Mer de Glace, but its power has gone by then, stolen by the West Face of the Dru.

All of us who have climbed there have felt that power first hand in the terrible clatter and whistle of the daily rockfall. In 1997 most of the central part of the West face exploded off and fell down, and the wall as we knew it changed completely. I saw the pale grey scar from the Plan des Aguilles in 2001, and didn’t recognize any of the features. By then, though, they had re-equipped the American Direct and some Russians had climbed a “new” route where the Harlin/Robbins line had been. But it wasn’t the same: the fantastic red pillar of the French Direct that had cleaved the wall for half of its height had gone. The pillar lay buried under thousands of tons of rubble on the Dru Glacier far below. And then on the 29th June 2005 the rest of it – the upper part of the West face and the Bonatti Pillar – came crashing down, altering the skyline profile of the Dru forever.

They say that catastrophic rockfall of this nature is just a natural phenomenon caused by the exfoliation of freeze and thaw cycles and is normal for such a young set of mountains, but global warming has added to this toll. In only 20 years, and I’ve seen it with my own eyes; the glaciers have retreated, the winter snowfall is half what it used to be, and the hotter summers bake the already unstable rock and melt the ice. The Alps are much drier now. And this acceleration has all ended at the flashpoint of the West face of the Dru. Three times in the last 20 years the mountain has shed its skin like a monstrous geological reptile, each time leaving a new skin in its place: a new facade of fragile and loose pale grey rock.

When I first saw the Dru I wanted it. All. Like an addict, I wanted to climb every route on that beautiful slender spire. I wanted to possess it, to have it, to have done it, and to make it mine. In another life I suppose I would have been a paedophile lusting after an underage Lolita, or an impulsive gambler slipping coins into the slots, or an irredeemable alcoholic, but climbing channeled this latent desire onto a steep and shadowy rockwall alternating orange buttresses and dark grey dihedrals. Instead of women, money or drink, my hands caressed sharp granite as the air dropped away beneath my feet. Eventually, I ended up climbing most of the routes on the Dru, possibly because I had to, or was compelled to, but also because the Dru represented to me the archetype of beauty and mountaineering perfection at the time. I have always been enraptured by beautiful and definitive mountains; mountains which are hard to climb on all sides, because that’s what I believe real climbing is all about. To me that is the art of climbing.

But even so, despite the many thousands of metres of climbing and descending, despite the beautiful pale orange cracks and the long grey corners, and despite the snow and the ice and the bad bivouacs, it isn’t the climbing that I remember so much as the people who I climbed with and shared all of those intense moments. The Dru as we knew it then has gone and so have most of those people too. When I think of the Dru now, though, I always think of Jarda, but that comes later.

My first foray onto the Dru was with Mick Hardwick. We climbed the American Direct up to the Jammed Block with Richard Behne and Paul Leslie-Smith. I wanted to continue. Just above I could see the 90 meter dihedral beckoning strongly, but it was a good foretaste and we hadn’t really prepared to continue. We rappelled down, threading our ropes through thick bunches of tat because the route would only get bolted later that summer. A year later, I would spend several weeks with Mick, cragging in the UK. He was long, lean and supple on the rock and searingly witty in the pub. At Tremadog and I saw him hold on for dear life on Strawberries and fight with every ounce of strength that he had and all he said afterwards was: “Good innit?” We climbed at Pembroke, Gogarth and Llanberis pass. We drank our pints of tea at Pete’s and then went climbing in the slate quarries. Mick was going to spend the summer guiding for ISM in Switzerland followed by a trip to Pumori that Autumn. I was going to the Alps for as long as it took. I shook his big hand goodbye in Gwynedd and never saw him again. He caught the Twin Otter from Kathmandu to Lukla en route to Pumori but the plane never landed. Apparently the engines failed. All they found were some melted carabiners in the smoldering wreckage deep in the tangled undergrowth of the Dhud Khosi gorge. Mick was 26 years old.

When I returned to Chamonix I knew exactly what I wanted to do. I didn’t even stop to pitch my tent before toiling up the long slopes to the Charpoa Hut in the midday heat. I bivvied at the crest of the Flammes de Pierres and fell asleep with the Bonatti Pillar a few hundred meters away across the chasm. I soloed the route just like Bonatti had done 32 years earlier, except the route was well known and well travelled and it took me 2 days instead of a week. I roped every pitch calmly and methodically, bivouacking 12 pitches up on an excellent ledge beneath an overhang. I fixed one pitch higher to the site where, the previous year Joe Simpson’s ledge had collapsed while they were sleeping on it. I wondered why they would have stopped there, of all places, when there was such a good ledge below. The full white moon rose over the Tafelere out of a deep purple sunset. I looked out over the wilderness of rock and ice and thought, yes, this is the place I want to be. I reached the summit easily the next day and was content, if only briefly, until I looked back up from the valley and saw the skyline.

There must have been a certain irony in the fact that I first ran into Jarda on the Dru. Dave Litch, my Scottish climbing partner, and I were slowly hiking up from Montenvers bound for the complete American Direct when we passed two obviously East European climbers coming down. They had that slightly dazed and disappointed manner which meant that they had had an epic or a struggle or hadn’t managed to get up a route somewhere. Dave and I continued up to the top of the Dru, with the 90 meter dihedral being as good as I had expected. Jarda and his partner continued down after what I later learnt was an epic in the Dru couloir with running water in the middle of summer. Some weeks afterwards, Jarda came up to our camp in Pierre D’Orthaz selling down jackets and titanium ice screws. He was a big man with Slavic cheekbones and red cheeks and a physique perfectly suited to carrying huge packs in the mountains. Jarda Gorjeck was Czechoslovakian and spoke no English, but I saw the fire and determination in his eyes. It’s hard to miss when you recognize your own kind. I saw big mountains in his future.

Greg Child once wrote an article entitled “Between the Hammer and the Anvil” about the phenomenal success of Eastern Bloc alpinists. After bartering, trading, fiddling and scheming to break through the Iron Curtain, the consequences of failure on a route in the West were huge. It was their ticket to freedom: they couldn’t fail, so they simply went for it, consequences be damned. With their backs up against the wall, a whole generation of these climbers did some of the boldest ascents ever in big mountains all over the world. It also wiped nearly all of them out.

We westerners are sissies in comparison. I saw the resolve in Jardas eyes, but declined the purchase. I couldn’t have known it then, but it wouldn’t be that long before I would be the one twisting those titanium screws into hard winter ice.

I went up on the Dru again and soloed the French Direct which wasn’t well known or well travelled, having only been done four years previously by Christoffe Profit. After seven pitches and a bivouac I broke through a roof onto the long vertical orange pillar. There was a vague crack running up the middle of it and seven more interesting pitches on aid put me onto a narrow ledge at the very top of the pillar. I bivouacked there and the night was calm and windless. The pillar dropped away into the inky depths of the Bonatti couloir, the lights of Argentierre twinkled far below, and I felt happy in my solitude. The next morning I joined the Robbins route for 6 pitches up loose, wide cracks and broken chimneys to the summit. The now familiar rappells took me down to the Charpoa and then down, down the Mer de Glace glacier and the Montenvers trail and down to the heat of Chamonix with aching shoulders and feet white hot and burning inside my Koflachs.

The very next day Julie Brugger walked up to me as I sat against a tree and said: “Hi. I heard you’re looking for a climbing partner.” It was to be the start of a long relationship and lifelong friendship. One of the first routes we did together was the North Face of the Dru. We bivvied at the top of the Niche after a day of treacherous mixed climbing in poor conditions. Just before dark I walked over to the edge of the west face and peered over. A thousand metres of steep granite plunged straight down onto the Dru Rognon below. Not far from where I stood I saw an old rusty bolt, and I knew immediately that it was Gary Hemming’s. These mountains are suffused with so much history that sometimes it’s hard to escape from it. Hemming had rappelled from this point all those years ago on a dramatic rescue to reach some injured French climbers, long before the helicopters or the Secours de Montagne could fetch you from pretty much anywhere in the Alps. Hemming eventually shot himself in Paris the year I was born. He had been depressed and a little bit crazy, but I have no doubt that the Dru had captivated him just as it had captivated me. Julie and I carried on to reach the summit the following afternoon in the mist. There was no wide vista of the Jorasses, the Midi or the Chamonix Aguilles, only a dim awareness of the bulk of the Grand Dru just behind. It was my fourth trip to the summit in two months. My thirsty desire for the Dru had almost been slaked.

That winter Dave Litch was killed while skiing in the Cairngorms. A slab avalanche overtook him but it was too late. He was an aspirant guide, a patriotic Scotsman and a fine climbing partner. We climbed winter ice on Ben Nevis and shared a doss in London. Nowdays whenever I hear Mark Knopfler’s song “On Every Street” it reminds me of Dave: the dapper mountain man and the suave, streetsmart cad that he had once been. Another young life was cut short by the snow.

I stamped the snow off my boots as I entered Snell Sports in Chamonix, the fug of central heat in the shop instantly warmed my face. The wide plate glass windows shut out the leaden grey skies, thick snow and the deep February winter outside. There was Jarda, red cheeks glowing in the warmth. His English was still non-existent, and his French not much better: “Escalade?”. “Oui.” And it was sealed. A few days later we clipped into our skis on the Midi and glided down the Vallee Blanche with hoards of other skiers. We turned off to traverse below the Dent Blanche and skinned up to the Shroud on the Grandes Jorrasses. We climbed that long sheet of ice with our skis strapped to our packs and descended into Italy, hitching back through the Mt. Blanc tunnel. Neither of us had Italian visas, but why do you need a visa if you’re leaving the country anyway?

Jarda was camping in the snow and I secured him a warm berth at the already overcrowded apartment of Gary Kinsey, a British friend of mine, who had rented a tiny place in Chamonix Sud. There was never any room to sleep which was usually impossible anyway due to the frequent parties and countless visitors from the UK. Jarda and I packed for the Dru Couloir in the corridor using sign language as drunken Swedes stepped over our gear.

From Grandes Montets we post holed down onto the Nant Blanc glacier. The day was crispy blue and cold like the inside of a deep freeze. Everything was clean and white like a glittering fairytale. We crossed under the Aiguille Sans Nom and finally the couloir came into view: a narrow gash splitting the North Face. It was the first time I’d seen it properly. The ice was thick and white and very steep. The whole of the Dru was plastered. It looked amazing.

“OK?” “Ok.” That was more or less the extent of what we could say to each other. Jarda burrowed through the Bergschrund and into the couloir. He was rock solid on ice and very strong, and in a way it was a pleasure to climb with someone like that, even if we couldn’t say anything to each other. The first three pitches were very delicate, thin plate ice over slabs and above that the couloir opened up as we climbed up on loose powder over hard ice leading up towards the “Breche” where the real climbing began. We became part of that cold blue and white world. The ice was brittle: each blow with the axe fractured the ice and sent it raining down on the belayer, quietly freezing below. The couloir narrowed. The climbing was steep, mixed, exhilarating and technical because of the blanket of dry powder that covered everything, but there was plenty of gear if you could find it beneath the snow. The rock walls closed in on either side. We reached the Fissure Nominee and it looked desperate. Four inches of ice choked up a vertical crack. A few feet above the belay I managed to hang precariously and twist a screw into the ice in the crack. It was halfway in when the ice all around it splintered, turning the screw into a dodgy nut instead. I was getting more and more pumped so I hung on it and somehow it held. I carried on up in this manner: some free moves, some aid, butchering the ice in the crack because we didn’t have a #4 friend as Jarda waited wordlessly in the shadows in his overstuffed down parka. An awkward move to get out of the crack at the top gained me a hard groove slickly veneered with verglas and powder snow. I eventually reached the belay which was an old peg at a ledge just big enough to stand on. Hours had flown by and the day had vanished. Grey wispy clouds streaked the sky and the Nant Blanc ridge briefly flared purple as night settled onto us with a deep blue hush. Jarda followed as I scanned the gloom above. All I could see was steep ice, and everything below was even steeper. Bivouac prospects looked bleak. I knew we were in for a long and grisly night.

It was pitch dark when he arrived at the belay, covered in spindrift with ice encrusting his face. “Bivvy here OK?” “Ok.” We each retreated into our own worlds as we prepared for the night. I rigged a suspended platform using my pack, my axes and some slings that I could sit on and draped myself saddle-like into my horse for the night. My sleeping bag came up to my waist and no further and my one leg kept falling asleep, but at least I managed to get my boots off. Jarda fashioned something similar and we both half hung, half sat and half stood as the night froze hard. Jarda held the stove in his hands while we made a brew and afterwards I looked at my watch and it was only 9 o’clock.

The night was interminable. It was impossible to get comfortable. We dozed and thrashed and wriggled and shook and shivered. The wind came up and blew spindrift on us and the dark starry night sucked all the warmth out of us. It was a night I’ll never forget.

It took an age to get going in the grey light of morning. The rush of blood to my hands was excruciating after I finally left the stance, but I did warm up and as luck would have it, there was a decent ledge just a pitch higher around the corner to the right. One more tricky crack with a few aid moves put us into thicker solid ice as the couloir continued relentlessly up. Eventually the angle eased slightly and opened up to easier ground. We climbed up cracks and over blocks and everything was covered in loose powder snow, making it slow and hard to find the right way. We reached the summit and the sky had become veiled with cloud. I felt very isolated standing there on top of the Dru, very far from home, in a cutting wind ahead of the approaching storm and the world sharp and jagged and white as far as I could see. We spent less than a minute on top.

They leave a section of the Charpoa hut open in winter. It’s a dark hovel and there was ice on the floor, but to us it seemed like paradise. Jarda found two cases of 1.5 L Orangina soft drinks in the hut storeroom that had been stashed away for the following summer. They were frozen solid, but we made Orange flavoured pasta and fell asleep warm and flat and comfortable. It was snowing the next day as Jarda loaded up his 20 bottles of frozen Orangina and we waded down through deep snow to the Mer de Glace and another bivouac at Montenvers and then down the trail to Chamonix under pines laden thick and heavy with snow.

“OK Jarda?”

“Ok.”

“C’est bien?”

“Oui.”

I had finished with the Dru. My desire had been slaked at last. In 1989 the velvet revolution opened the Czech borders but Jarda had long since gone. I don’t know where he ended up in the end, but I did hear via the grapevine that he had taken on a job doing some of the most horrible work imaginable: cleaning out the inside of tanker trucks. They would lower him down inside with a respirator and a light and he would pressure wash, sandblast and repaint the inside of the tanks. That winter in Chamonix Jarda and I hung out sometimes during the bad weather when it was too bad even to ski. One of the things he liked to do was to go into the supermarkets, the climbing stores and the bricollage shops just to look: not just at the vast array of shiny consumer goods available, but also at the boxes and boxes of stocks packed on the shelves. He said very little, but his eyes said it all. Perhaps it was because he couldn’t speak our language, but he always looked haunted and hungry and resolute. This was a land of plenty and he saw it every day in silence. I don’t know where he came from or anything about his family or what he had left behind, but he was a good climber and he had done a lot of routes in Chamonix. We had spent a total of seven days tied into a rope together without being able to speak a single word to each other, but still that didn’t matter at all. I hardly knew him, but he made a big impression on me.

Jarda was killed in 1994 on Dhaulagiri. They were trying the huge and dangerous South face of D IV alpine style; a bold and dangerous attempt. Apparently the whole slope they were climbing on avalanched and they didn’t have a chance. Their bodies were never found. Jarda is gone.

I sometimes wonder where he would be now if he was still alive, but perhaps his destiny and the big mountains had been locked together right from the start.

There is no doubt that in the years to come, routes will get climbed or reclimbed on the new Dru and those in turn will add another layer of legend to a mountain already rich with history and effort. Time has moved on. Like turning the page of a book, in one sweep a whole chapter has been erased. Walter Bonatti is an old man now, most probably resigned to the fact that one of his masterpieces has gone, but in the end it doesn’t matter. We spent our youth chasing dreams and we found them, on the Dru and elsewhere. If Alpinism is a form of poetry, then the mountains onto which we wrote our lives was just a medium, a transient page, only we never expected to see it change so quickly within our own lifetimes. What we had once thought of as something much more permanent than ourselves has gone now, an experience that I imagine would be similar to the early death of a parent, although I wouldn’t know that for sure. I loved being on the Dru: I loved the lightning rod-like conductivity of raw mountain power that the peak exhaled. I loved the wildness and the steepness and the history of all of those who had been there before. I loved the feel of the rough alpine granite and the blue shadows of early mornings on the wall, and I feel a sadness for my friends who were there with me at the time, not because they are gone now, but because of how much life they missed out on in the futures that were never to be theirs. Life goes on. It always does. It always turns out in the end.

There are five requirements for a lonely bird:

The first is that he flies to the highest point,

The second that he doesn’t yearn for company even of his own kind,

The third that he points toward heaven,

The fourth that he has no specific colour of his own,

The fifth that he sings very softly.

San Juan de la Cruz