WORDS BY MARISSA LAND

PHOTO BY TOBY SAXTON

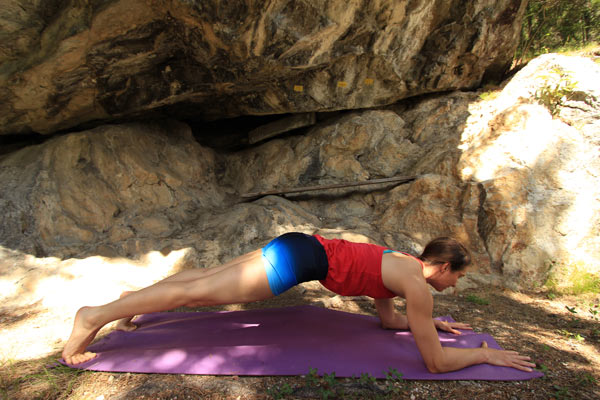

The words ‘core strength’ are used a lot in the climbing training scene, and I think it’s safe to say most climbers understand that good core strength is essential for becoming a better climber. But what is ‘the core’ and how does it enhance our climbing performance?

Without getting too anatomically complicated, our core is comprised of the deeper muscles of our lower torso and pelvis. If you’ve ever heard anyone say, ‘keep your tension’ or ‘keep it tight’ it all refers to the same thing: the activation of our deep postural/stability muscles in the central part of our body, or our ‘core’.

If you were to look at an anatomical image of the core, it would most likely reference the multifidus, diaphragm, transverse abdominals and pelvic floor muscles. These muscles form an internal ‘cavity’ that links the pelvis, ‘tailbone’, ribs and spinal segments. Being deep postural muscles, they are designed to make relatively small movements, but hold a contraction for a long period of time so they can support our joint structure to which they are intimately related (e.g. our multifidus joins each spinal segment). This means that when our core is strong and stable, our spine and pelvis are also supported.

OUR CORE AND CLIMBING

The core is really our power centre for explosive movement and tensional strength when climbing. A stable core works as a stable ‘platform’, allowing optimal transfer of force between our upper and lower body. So, the stronger, more stable our core, the more power we can create. When the core chain breaks down, force transference and energy is lost through compensation and wasteful movement patterns. Every movement we make when climbing, every drop knee, back step, high step, rock over, dead point, dyno, lock off, heel hook, etc., becomes a lot easier when our central core is both strong and balanced. Movement becomes controlled, lighter and you fatigue less.

But the core is not just important for creating more power, it’s also important for preventing climbing related injuries. Let me give you an example. If the core is dysfunctional (e.g. weak pelvic floor muscles and dysfunctional diaphragm), the hip joint, which is designed for rotation, flexion, extension, abduction and adduction, may become misaligned and undergo shearing forces and impingement. Over time, dysfunction may set in, muscle actions may become imbalanced, compensatory and unstable movement patterns may evolve, and joint weakness and pain may be experienced. So, a strong and stable core can reduce the risk of climbing related injuries in our shoulders, hips, wrists, etc., and maintain healthy movement patterns throughout our body.

Subscribe to get your hard copy or read online.